This short story was bought by Zombie Works for their monsterthology, published earlier this year. I hope you enjoy it.

The dark chill that lurked between the trees seemed to mock her. Someone or something watched her every move. The constant staring caused a crawling sensation. It tugged at her braided hair, slid down her back and tingled the skin on her legs. As the gaze moved, and the slithering of it reached her thighs, she spun round, glaring, hoping to catch the culprit. Nothing moved. Not even a blade of grass. The still evening hung silent. The birds had ceased their twittering, mute, as dusk crept over the hills.

An owl hooted and broke the silence, ‘more pawk’ - ‘more pawk’. Its sad call went unanswered. She stood still and looked around, daring the observer to show himself. Not a ripple broke the mirrored surface of the black lagoon. The new moon’s crescent seemed painted on its surface. Her heart beat thumped in her ears as apprehension gripped her. How stupid to be out this late, yet gathering herbs and leaves on the rising moon ensured better results with her ointments and tinctures. She picked up the sack full of Kawakawa leaves. Many had holes, which her mother had taught her, showed that the insects knew the best leaves to eat. Funny how her mother’s comments returned to her mind so frequently. It had been ten years this spring since she’d died and Amelia had inherited the cottage. A failed marriage had left her homeless and she’d returned, grateful for the inheritance and happy to be back in the fields of her childhood.

This evening, after picking Kawakawa, she’d gone searching for Horopito bushes and had wandered deeper than usual into the forest, coming out on the far side at the edge of the lagoon. The waterfall thrummed in the twilight, its spray keeping the surrounding foliage moist and green, Horopito loved the dappled sunlight there. She harvested the slow-growing shrubs lightly, packing the precious leaves in a small bag on top of the Kawakawa’s bulk.

Now she needed to find her way home in the gloom. Perhaps the safer option would be to skirt the edge of the forest rather than go directly through the trees. There’d always been tales of a monster lurking in the shadows near the water’s edge.. Memories of forgotten nightmares surfaced; dark shapes with mouths dripping blood, a sense of suffocating, waking - screaming. Her heart thumped in her chest and a panic attack tightened like a band around her throat. She stumbled, gasping and hurrying, not watching where she placed her feet.

Her shoes sank into the grass, the ground grew boggy, much wetter than the last time she passed this way. She hoisted her bag of harvested herbs tighter on her shoulder. The new swampy morass could be overflow from the poisonous pond. To fall and land the herbs in io the squelching sods would ruin their purity.

The lagoon had been a bubbling, septic sinkhole for as long as she could remember. No matter how many times the village children fell ill, still they dared each other to defy the Taniwha who lived there. Unseen, evidenced only by the ripples it left and the bubbles plopping from its breath, the Taniwha, they reckoned, turned the pond into a smelly soup, In high summer a green scum formed a crust and the children thought they could walk across the surface. Falling in didn’t result in them being eaten by the monster. Their screams were apparently enough to scare it away, they said.

Sadly, any child who floundered in the muck usually succumbed to its foulness, and then the villagers would bring their ill offspring to her. They bartered and begged for her tinctures, ointments and Horopito tea. Mostly, the remedies worked, but occasionally a youngster would die from swallowing the foul liquor. The toxins gave them hallucinations and their screams of fear as they vomited black bile were the saddest things she’d witnessed.

She suspected arsenic and lead were the root cause. These leached from the tailings of an old mining operation above the lagoon. The toxins created the gases which moved the thick fluid. Tales of a monster were folk lore, passed down from generation to generation.

After a child’s death the forest would be quiet, the game abandoned. When the children’s fear faded, the challenge of a dare and the delicious anticipation of terror, drew the children back, to walk the log that once grew beside the foul slurry.

Amelia tired of warning the youngsters as they passed her cottage. She’d wearied too of their taunts and curses, calling her a witch and a hag. Yes, her clothes were old and her hair long but she kept it braided. She walked tall, aware that to stoop would add to the image of a witch.

At last, the outline of her cottage grew from the shadows. The moon had risen as she’d hurried back. It showed the peak of the roof and reflected in a window, like a lamp on a windowsill. Her breathing eased.

Her mother built the cottage so that it nestled against the rock wall. Unknown to the villagers the back of her house, abutting the rockface, sheltered a small spring. The water trickled from a fissure onto a stone, worn smooth over eons to form a basin. This water was the base of her medicines. It had a sweet clarity, as if the water sprung untouched from the depths of the earth to become a life force, a well of goodness in her world of ofttimes despair and pain. The failed marriage had left her with injuries too deep to be seen but she found the solitude and security of the cottage healing.

She hurried, unlocking the wooden door, swinging it shut, locking it and putting the bar across. Only then did she take a deep slow breath and try to analyse the fear the forest had caused; the sensation of being observed, the suspicion something followed her. She shook her head to dislodge the folly of old memories, of childhood tales, of seen and unseen horrors. On a clear night, with moonlight and stars winking above, why had she been frightened?

After a hot herbal drink, she slept in her chair, only to be woken by the sound of scratching. Intermittent; soft then hard, long scritches followed by tapping. It woke her, but exhausted from her day of foraging she slipped back to sleep, blaming a branch against a window, until the noise became part of a nightmare. She woke again – gasping - relieved to be awake.

Now the sound became insistent. Not a branch, but outside her front door. No adult or child would behave like this. An animal perhaps? Injured and flailing around. She picked up the heavy rod by the door and slipped the chain to peep out.

AT LAST, YOU WAKE!

A voice rang in her head, forceful yet not loud enough to make her ears ache.

She replied mentally, her eye to the gap. “Who am I speaking to?

IT IS I - THE TANIWHA. I NEED YOUR MEDICINE. I AM INJURED, POSSIBLY DYING. IN THE NAME OF THE FOREST GOD, TANE MAHUTA, I BEG YOU FOR CARE.

A Taniwha? At her door, in the middle of the night? Surely, this was part of her dream. She pinched herself, hit her shin with her rod and winced when it struck. Not dreaming after all. Bile rose in her throat. Should she meddle with the unearthly? Was her life in danger by opening the door? A large eye peered back at her, green as a new shoot yet pink where white should be, like a budding Horopito leaf. Definitely not human.

From the size of your eye, you are too big to fit in my house.

I CAN SHRINK TO FIT. I PROMISE YOU LONG LIFE IF YOU CURE ME.

And if I fail to cure you, will you kill me? If she had spoken these words her voice would have wavered, but in her head she sounded bold.

NEVER. YOU ARE A HEALER. I HAVE WATCHED YOU. I KNOW YOU WILL DO NO HARM. PLEASE – TIME IS PASSING. MY BODY FAILS.

What else could she do? He’d probably hang around until he died and then how would she dispose of the smelly remains? Besides, she may never get another chance to meet a Taniwha. Perhaps this foolishness was the result of too many herbs in the tea. If this was a dream then she’d wake up soon – and she slipped the chain and opened the door,

In front of her towered a huge creature, black as the night except for where the moonlight touched its scales and their edges shone iridescent green. His snout was elongated, his ears pert and his eyes protruded. He would have been very scary except for the tears that slid down each jowl and hit the porch floor, landing with loud plops in the puddle already there. Her heart turned, compassion overcoming fear.

You’d better come in, after you’ve downsized.

His sigh moved like a soft breeze, warm on her cheek as it swept past, carrying a waft of decay that confirmed her suspicion.

Have you been playing in the lagoon? Don’t you know it’s poisonous?

OF COURSE I KNOW. WE ALL KNOW THE POND IS POISONOUS. WHY ELSE WOULD WE FRIGHTEN THE CHILDREN AWAY? I FEAR IT HAS SEEPED INTO MY HOME AND CONTAMINATED MY DEN.

The water dragon trembled and emitted a high-pitched hum, and then began to shrink in size. As it grew smaller it became less frightening, Finally, a black, scale-covered, horse-sized Taniwha, its tail sweeping back and forth, its front legs flapping at her, indicated she should open the door further. Now she had a bossy, horse-sized Taniwha to treat, Plus, from his use of ‘we’ in his statement, there was more than one of him in the world hereabouts. Did she want a new clientele?

. I WILL HAVE TO FIND A NEW HOME IF I SURVIVE THIS POISON.

He lumbered across the threshold, filling the entranceway, which wasn’t designed to accommodate water dragons, even a small one.

I will do my best, but you must also want to live, and you will need to stay within the back room, be silent and not be seen by anyone. Sometimes I have visitors, requesting my remedies, as you are doing. If you are seen then we will both be killed by the villagers who believe in monsters and witches.

I WILL DO ANYTHING YOU ASK OF ME.

She led the creature down the central hallway to the back room where the spring trickled its song down the rock wall. The Taniwha lapped the basin dry, and curled, his head close to the water source, filling the floor space.

I will get you some Horopito tea. It will take me a while to brew enough to satisfy your body. Please rest and please remove your pain from my head. I know you are ill. I do not need to share your agony. I need to think clearly.

Her headache faded, only to return with blinding force, from time to time, over the next three days. The pain would rouse her in the night, prompting her to stumble to the kitchen and prepare another brew, hoping to ease the Taniwha’s agony. Some of his scales fell off. They were like round leather disks, pewter in colour, the green gone, yet light to carry when she stacked them against the wall. Should one keep a Taniwha’s scales? Were they magical? Would he grow new ones? Weariness muddled her mind with silly questions.

Under the remaining scales, sores erupted, raw and angry, foul smelling and weeping. She lathered them with Kawakawa salve, made from sunflower oil that had seeped with the leaves for months. By adding beeswax and then cooling she formed an ointment she could spread with care. She burnt Rosemary stalks in the stove to mask the putrid smell that filled the house, and hoped she would not be bothered by villagers wanting her remedies.

By the third day she knew they were winning. They slept longer because his pain had eased and when she opened the door to the back room her black Taniwha had become an indigo bulk. Always when he slept his size increased, his ridged back touching the ceiling and each time he woke he had to shrink to make room for her to enter and tend to him. On this morning, he bared his teeth. Her heart leapt against her ribs and she clenched her jaw.

Don’t hurt me, I am trying to cure you.

I AM SMILING, AS HUMANS DO.

She smiled in return and patted his snout. You can be very scary at times. Just as well I have a strong heart.

A rumble shook the floor, the vibrations travelled up through her legs and into her skull. Not that unpleasant, and she assumed it was the Taniwha’s equivalent of a laugh.

What do I do with these, now that you are healing? She pointed to the stacked scales.

BURN THEM – and she did, adding them to the diminishing pile of wood and Rosemary branches.

On the fourth day several villagers knocked at her door. Three children were ill. They demanded she come. She refused, but passed them jars of Horopito tea through a window, with clear instructions. They returned the next day, angry that their offspring now had weeping sores on their bodies and cried with the pain. She knew that pain. She’d lived it with the Taniwha so she gave them salve and sedative powder, crushed from belladonna leaves, with strict instructions on portions.

Behind her the Taniwha shifted and the house trembled. The Villagers left, muttering, unhappy that she would not leave her cottage.

On the sixth day a small child knocked at the door, begging her to come to his sister. Two children had already died and his sister was failing. She wept, unable to explain her refusal. She gave him more salve and shut the door on his tear-stained face. Never before had she refused a child’s request, but she dared not leave the Taniwha alone. His skin had almost healed, a gleam had returned to his eyes, the pink gone. His indigo coat of scales grew bright green edges – but his legs folded whenever he tried to stand. He wasn’t strong enough to leave.

On the night of the seventh day the villagers returned carrying torches of burning brush, Angry shouts greeted her as she peered out. Their rage at the death of their children now focussed on her failure to cure them.

She protested. Her voice hitching, tears staining her cheeks. She shared their grief. She reasoned; sometimes her medicine wasn’t strong enough. They ignored her words, waving their flaming brands in her face until fear at their rage made her slam the door and bolt it.

After a time of silence, she thought they had left …and then smoke trickled in through the wallboards and up through the floor. A crackle of fire warned of her impending fate. Her mouth dried, fear tightened her chest and she staggered, wracked with unbelievable horror, down the passage. They were going to burn her alive.

She fled to the room with the spring and the Taniwha.

“What do I do?” she screamed at him. “I have saved you, now go out and scare those people away. Put out the fire. Do something—save us!

I COULD EAT SOME.

“There’s too many. They will kill you.” She clung to the door jamb, fear trickling down her legs, retching as the smoke filled the hallway and the crackle of the fire grew closer.

The Taniwha roared, his voice melding with the noise of the fire, and he smote the rock wall with his tail. Where the spring had trickled a stream gushed forth. The Taniwha drank huge gulps from the flow.

STAND AWAY. TAKE SHELTER.

He broke through the wall and up the hall, his bulk growing with each second. He sprayed the walls with water and the fire protested, shrank back, flickering, climbed again and died as the Taniwha stamped on the smouldering wood. He burst through the front of the house, roaring his displeasure, towering above the villagers, who now edged closer, waving their flaming brands in defiance.

The Taniwha stilled. The villagers crept even closer, then faster than a blink the Taniwha twirled, his tail whipping with him, flattening his attackers like the blade of a scythe. Those left standing, retreated, sheltering behind trees. In the moonlight fear riddled their faces, their shouts sounding puny against his angry roar.

GET WHAT YOU WISH TO SAVE AND CLIMB ON MY BACK

All her knowledge lay in her head. Anything else she needed could be found again in forest and field. She stepped gingerly from the ruins of her home and climbed his familiar scales to sit on his back.

YOU CAN NEVER RETURN.

I know. Thank you for saving me.

A new life beckoned. Her client seemed well on the road to renewed health and she now had a new line of customers. A wind rose to twist and howl around them and in its embrace she and the Taniwha transformed into a swirl of black smoke and merged with the trees.

Later, the villagers, having found no trace of her bones in the ashes, nodded confirmation of their decision to burn the witch alive. The Taniwha remains in folk lore, only now there are whispers of a woman who rides its back. The children swear it’s true. She warns them away from the lagoon where the monster hides and the surface ripples from his breath.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++

If you enjoyed this, you can read my ebooks here: https://www.amazon.com/author/derynpittar

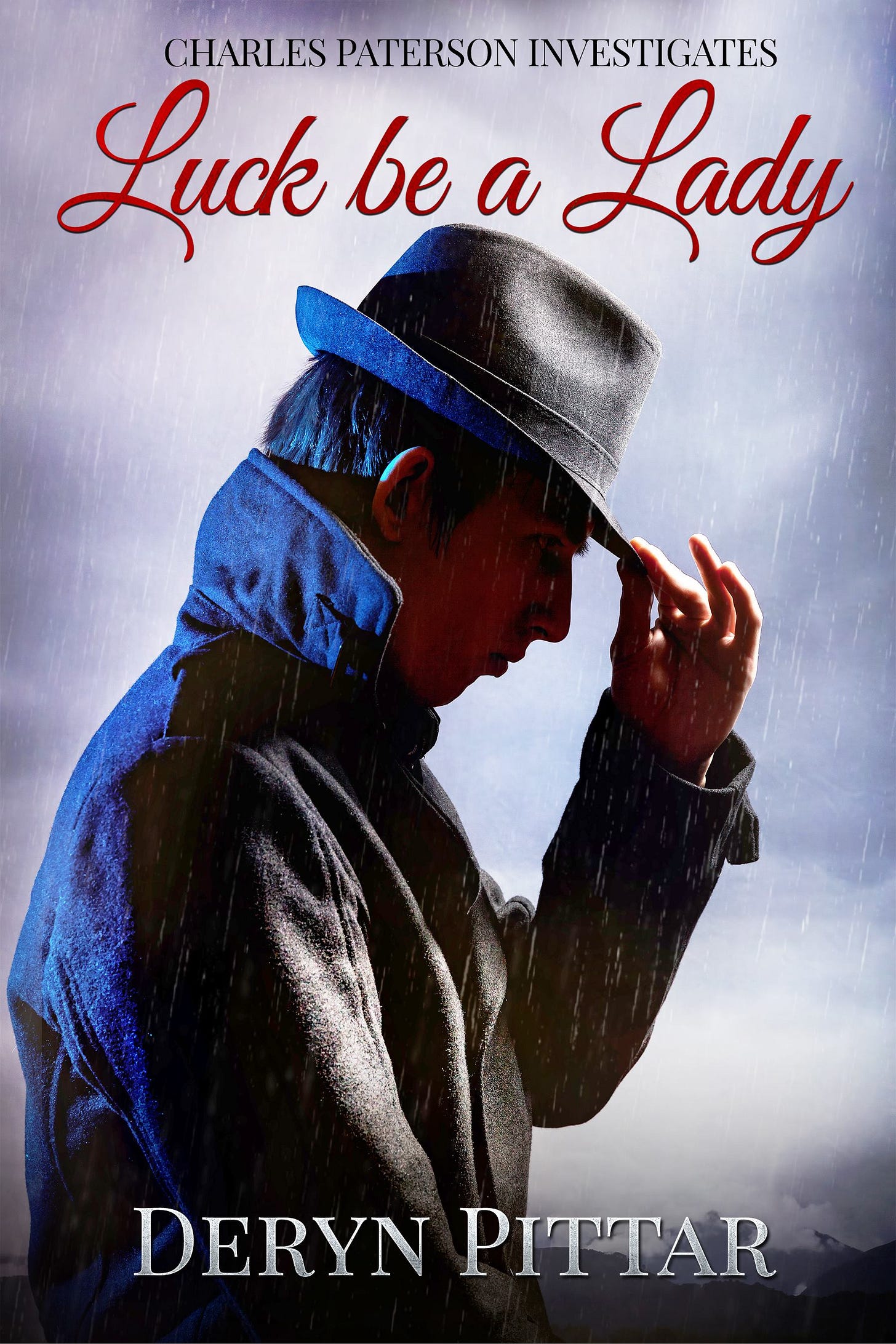

For those of you who love a cozy mystery, I’d recommend you read this:

Luck be a Lady-A small town cozy mystery.